Contents

The Life and Work of Clarice Cliff

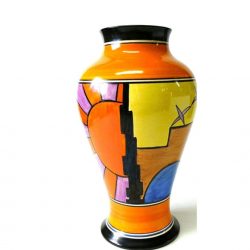

From humble beginnings, Clarice Cliff flourished to become one of the most influential ceramic artists of the 20th Century. Choosing to become a highly atypical “career woman”, Cliff broke the barrier that generally separated men and women in the workplace to become the Art Director for two adjoining factories in Burslem, Staffordshire by 1930.

Cliff’s ceramic designs are highly sought after, and are some of the best pottery examples of the Art Deco style, which was globally prominent between 1925 and 1950. Although the bulk of her creative masterpieces were created during the 1930s, Cliff continued to maintain a presence in the Burslem pottery works until 1963.

English Bone China

Though the British Isles have a long history of producing ceramic wares, the fine white ceramics we now associate with England were not developed until the mid 18th century. John Astbury and Thomas Whieldon of Staffordshire were the foremost potters of the period, with Whieldon in particular producing wares of pale-colored transparent glazes.

The two men led the way to the perfecting of lead-glazed pottery, a technology which had been the achievement of Josiah Wedgwood. By the mid 18th century, Wedgwood and Whieldon had been in a partnership for several years.

The resulting cream-colored lead-glazed earthenware, known by 1765 as Queen's Ware, was so successful that it competed with imported porcelain and was widely imitated throughout the country. This light coloured ceramic was the predecessor to the now widely recognized English fine bone china.

Bone china is a type of soft-paste porcelain that is composed of bone ash, feldspathic material, and kaolin. The traditional recipe for bone china was improved and perfected by Josiah Spode at his Spode pottery works in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire between c1789 and 1781. By the turn of the 18th century, commercially produced bone china was readily available on the English market.

From its initial development right up to the latter part of the 20th century, bone china was almost exclusively an English product and its production was effectively localised to the area around Stoke-on-Trent. Most major English firms made or still make bone china, including Fortnum & Mason, Mintons, Coalport, Spode, Royal Crown Derby, Royal Doulton, Wedgwood, and Worcester.

Art Deco Ceramics

Art Deco was an international style, which grew and developed in France beginning in the early 20th century, and flourished until the beginning of the Second World War in 1939. Elements of art deco continued into the 1950s, and art deco-influenced designs reappeared in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s.

Like Art Nouveau, art deco’s impact focused mainly on the decorative arts, including graphic arts, interior and industrial design, fashion, and architecture. Within the ceramics industry, the influence of art deco was of paramount importance, fundamentally changing accepted concepts of both shape and decoration.

The origins of the term art deco lie with a group of French artists known as La Société des artistes décorateurs, formed after the 1900 Universal Exhibition held in Paris. Their purpose was to promote the beauty and superiority of French decorative arts, and by 1925 resulted in the famous Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Art) held in Paris.

Art deco style is a blend of several different decorative influences including neo-classical, cubism, art nouveau, and others, and was initially characterized as a style that was opulent and elegant, but above all modern. Characteristic of art deco, and seen widely in art deco ceramics, are the use of geometric shapes.

Motifs widely used in art deco ceramic decoration vary but are particularly characteristic of the style, including stylized representations of the rising or setting sun, the chevron, and geometric patterns based on repeated lines of overlapping rectangular shapes. Stepped forms such as the ziggurat and pyramid were popular, derived from Aztec and Egyptian culture.

Clarice Cliff

Cliff was born in Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, England, on January 20 1899; one of seven children. She displayed a large degree of independence from a young age, possibly a product of being educated at a different school from her siblings. Having shown an interest in ceramic artistry, she started working at age 13 as a gilder, adding gold lines on traditional ceramic ware.

Having mastered this, she switched to learning freehand painting while studying at the Burslem School of Art in the evenings. Even as a young teen, Clarice Cliff was breaking the mould. Most young women in the Staffordshire potteries would apprentice a particular skill and, upon mastering it, would stay with that task to maximize their income.

In 1916, Cliff made the decision to move to the factory of A.J. Wilkinson at Newport, Burslem. This came hand-in-hand with a lengthy journey to work, but was a promising move in order to improve her career opportunities.

Cliff was ambitious and continued acquiring skills including modelling figurines and vases, outlining, enamelling (filling in colours) and banding (placing radial bands on plates or vessels). By the early 1920s, Cliff was brought to the attention of factory co-owner Arthur Colley Austin Shorter.

Shorter was 17 years older than Cliff and married, but eventually they formed a romantic relationship. In addition to being superbly talented, Cliff’s proximity to Colley Shorter came with certain advantages, and she was able to attend the Royal College of Art and journey to Paris to study design, funded by her work. In 1924, Cliff was given a second apprenticeship at A. J. Wilkinson's. \

She was frequently in collaboration with the factory designers John Butler and Fred Ridgway producing conservative, Victorian style ware, but eventually Cliff's wide range of skills were recognised. In 1927 she was given her own studio at the adjoining Newport Pottery (which Shorter had bought in 1920) and was able to decorate defective white porcelain ware in her own freehand patterns in a style called “Bizarre”.

Clarice Cliff Pottery

The new Bizarre line proved immediately popular, and Cliff was soon joined by a young painter to assist in production. Eventually, the term Bizarre was used as an umbrella name for Clarice Cliff’s entire pattern range, with the very first pieces produced being referred to as Original Bizarre.

One of the most popular designs designed and produced by Cliff was Crocus, which was designed in 1928 and instantly attracted large sales. Upwards of twenty young painters produced nothing but Crocus 5½ days a week, for much of the 1930s.

Cliff’s career progressed quickly and by 1929 her team of decorators comprised of nearly 70 painters, mostly young women referred to as the “Bizarre Girls”. The following year she was appointed Art Director to both Newport Pottery and A.J. Wilkinson. Despite the Great Depression, Clarice Cliff branded ceramics continued to sell in volume throughout the Commonwealth and the United States. It was stocked by such well-known brands as Harrods, John Lewis Peter Robinson, and Selfridge’s.

However, the onset of the Second World War meant that only plain white pottery was permitted under wartime regulations. Although Cliff continued to manage but was unable to continue her design work. After the war, tastes changed to a preference for more conservative, minimalist wares. Although she continued to run and co-own the factory until 1963, Clarice Cliff would never return to the creative work that had established her reputation.

Legacy

“Having a little fun at my work does not make me any less of an artist, and people who appreciate truly beautiful and original creations in pottery are not frightened by innocent tomfoolery.”

Clarice Cliff, 1931

The collecting market for Clarice Cliff pottery is complex. To this day, it is still possible to find examples of Cliff’s more common work for as little as $40-$60. Rare combinations of shape and pattern can bring tens of thousands of dollars and are highly coveted by collectors.

The fame and success reached by Clarice Cliff is difficult to appreciate in the modern era, given the many informal barriers at the time that she was able to break through.

“Career women” were extremely uncommon during her lifetime, and the publicity she received in the national press was unprecedented. During 1928 and 1936, 360 articles were written about Cliff and her work in a variety of media outlets including magazines newspapers.

Susie Cooper had fewer than 20 articles through the same period. Interest in Cliff’s life and work gained pace in the 1970s, and continues to be strong to this day. She continues to be celebrated as an ambitious working-class Staffordshire girl who brought modern art to the people.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.