In the world of Ming and Qing dynasty art, knowing how to look at a reign mark is a key asset for any collector, specialist, or enthusiast to correctly identify the date and the value of a piece of Chinese porcelain.Reign marks can be found on Chinese ceramics mainly from the early-Ming dynasty (15th century) through to the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

Contents

These marks are varied - they can be hand written, incised, or stamped (in the 19th century and later), and can be found in underglaze (for example on blue and white and copper-red porcelain), overglaze, or gilt enamels.

They are written in one of two scripts, kaishu, regular script (the font that we see in everyday use) and zhuanshu, seal script (a traditional script derived from ancient oracle bone characters).

As with traditional Chinese text, marks are read vertically from left to right. The characters are positioned either in a straight line, a square, or in two lines either horizontal or vertical.

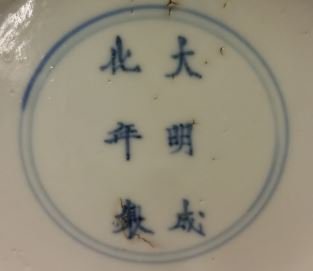

For example, a 6-character mark from the Chenghua reign (1465-1487) would read ‘Da Ming Chenghua nian zhi’ (大明成化年製) which would be translated as ‘made in the Qianlong period of the great Qing dynasty’.

- 大 da – Big/great

- 明 Ming – name of the dynasty

- 成化Chenghua – name of the emperor

- 年nian – year

- 製 zhi – made

Reign marks are not limited to Chinese porcelain – they can be found on anything from jades to lacquerware, from bronzes to cloisonné enamels. The position of the mark would depend on the piece itself, but generally speaking, for vessels like vases, bowls, or plates, it can be found on the base, but there are instances where pieces bear a single-line mark to the rim, or even on the interior.

For example, the earliest reign marked pieces are attributed to the Ming dynasty Yongle, Xuande, and Chenghua period, and those marks could found on the interior of vessels such as stem cups and bowls.

In its purest sense, the reign mark indicates that the particular piece was made during the time of and for the court of that particular emperor. There are two types of Chinese ceramics – guanyao (porcelain made in the Imperial kilns for the royal court) and minyao (porcelain made in commercial kilns for the people).

Both types of porcelain can bear reign marks, however, as the imperial kilns employed calligraphers who specialised only in the writing of these marks, guanyao marks tend to be of a much higher and more consistent aesthetic quality, and nowadays seen as more valuable.

Don’t make the mistake of determining the age of a piece solely from its mark. It can be said that the majority of items on the market bearing reign marks are not of the period they are claiming to be. That does not necessarily mean that the particular piece is a modern fake, as it is not uncommon for a piece to bear the mark of an earlier emperor.

These are ‘apocryphal’ marks, and they were used as reverence to an earlier emperor and admiration for the art that was created then. For example, a vast number of Kangxi period (1662-1722) pieces bear Chenghua (1465-1487) marks because he was revered in the 18th century for high quality of his imperial porcelain. And many 19th century pieces are adorned with Qianlong period (1736-1795) marks as a reference to the exquisite standard of the porcelain produced at that time.

Being able to recognise the style of these marks and combining it with an assessment of the rest of the decoration is a key tool in helping one to determine the date of a piece. For example, knowing that it is rare to find a Kangxi mark in zhuanshu seal-script during the Kangxi period (1662-1722) will help you identify the piece as 19th century or later.

Or the fact that marks which are stamped rather than hand-painted are more commonly found in later 19th century and 20th century porcelain, so seeing a piece bearing a stamped Qianlong mark would point towards a later date.

It must be said that some perfectly genuine pieces will not have reign marks, or perhaps will not have a mark altogether. Knowing this information can also be incredibly useful – for example, the early part of his reign, it is believed that Kangxi emperor issued edicts restricting the use of his reign mark for all but the best imperial wares, so instead, potters made do with replacing the mark with auspicious emblems such as an artemisia leaf, ruyi sceptres, rabbits, beribboned scrolls, or ding censers, or even just an empty double circle.

These restrictions were eventually loosened, so Kangxi mark and period pieces can still be found today.

You may have heard of the term ‘mark and period’. This means that the piece was made during the reign of the emperor of whose mark it bears. In the current antique market, a piece of Chinese porcelain with the ‘mark and period’ designation, especially with regards to commercially ‘popular’ emperors such as Yongzheng or Qianlong, this could potentially add another (or a few other) digits to the value!

An extreme example of this situation is: a blue and white hu-form vase dated to the 19th-20th century with an apocryphal Qianlong seal mark was sold at Christie’s South Kensington, 29 February 2012, lot 804 for 4,750 GBP (including buyer’s premium). Compare that result with a blue and white hu-form vase.

With a very similar decoration however with a Qianlong seal mark and dated of the period (1736-1795) which was sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 30 November 2016, lot 3329 for a whopping 1.5 million HKD!

There are no hard and fast rules when it comes to attributing a date to a piece of Chinese art –unlike contemporary art, individual artists didn’t sign their works, so in this field, knowledge is key. When presented with a piece of porcelain, a true connoisseusr will take into consideration not only the reign mark, but also the overall shape, design, and quality of the porcelain to determine its age.

With the understanding of reign marks and their usage through the centuries a collector will truly develop the skills to determine whether a piece is indeed ‘mark and period’.

Reference links:

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

Hongwu (1368-1398) |

Yongle (1403-1424) |

|---|---|

|

年洪 製武 |

年永 製樂 |

Xuande (1426-1435) |

Chenghua (1465-1487) |

德大年明 製宣 |

化大年明 製成 |

Hongzhi (1488-1505) |

Zhengde (1506-1521) |

|

治大 年明 製弘 |

德大 年明 製正 |

Jiajing (1522-1566) |

Longqing (1567-1572) |

|

靖大 年明 製嘉 |

慶大 年明 製隆 |

Wanli (1573-1619) |

Tianqi (1521-1627) |

|

曆大 年明 製萬 |

啟大 年明 製天 |

Chongzhen (1628-1643 |

|

|

年崇 製禎 |

|

Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)

Shunzhi (1644-1661) |

Kangxi (1662-1722) |

|---|---|

|

治大 年清 製順 |

熙大 年清 製康 |

Yongzheng (1723-1735) |

Qianlong (1736-1795) |

|

正大 年清 製雍 |

隆大 年清 製乾 |

Jiaqing (1796-1820) |

Daoguang (1821-1850) |

|

慶大 年清 製嘉 |

光大 年清 製道 |

Xianfeng (1851-1861) |

Tongzhi (1862-1874) |

|

豐大 年清 製咸 |

治大 年清 製同 |

Guangxu (1875-1908) |

Xuantong (1909-1912) |

|

緒大 年清 製光 |

統大 年清 製宣 |

| Author - Denise Li | Denise is an independent Chinese art consultant who gained her experience as a Specialist at Christie's in London, UK after completing her studies in Chinese archaeology. She is currently providing specialist services to various auction houses and enjoys sharing her knowledge through writing for Antique-Marks.com |

Dimi

Reign Marks

Jasmine Holt

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/a3d1ed8380342297055c15423066464c09c0f63fea2ea4c985ecdb7505bea214.jpg

Can anyone help identify this please?