Porcelain from the Kangxi period (1662-1722) is one of the most recognisable and ubiquitous areas of Chinese ceramics. Ceramics from this reign are found in collections and museums all over the world, so it is well worth familiarising oneself in the shapes, decoration, and marks on pieces of this prolific period of porcelain production.

Kangxi emperor (康熙lived 1654-1722, reigned 1662-1722) was the second emperor of China during the newly-established Manchu Qing dynasty. The Manchu people conquered the preceding Ming dynasty, which was ruled by the Han Chinese.

Kangxi is seen as one of the greatest Emperors of China for his: educated rule; suppression of rebellions; patronage of literary, scientific, and artistic developments; and he, in essence, ushered in the “High Qing” period of prosperity and peace.

An important milestone in the timeline of Chinese ceramics is the reopening of the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen, which were largely neglected during the decline of the preceding Ming dynasty. These kilns, in addition to the new technologies gained by the Kangxi emperor’s welcoming relationship with the Jesuits, resulted in an imperial and commercial porcelain industry which both refined traditional techniques and encouraged the development of new designs and palettes.

The words ‘Kangxi porcelain’ will most likely evoke images of two distinct palettes – blue and white and famille verte (a quick internet search will also confirm this!). Of course, these are only two of the many developments in glazes in Kangxi-period kilns, but we will begin the discussion here.

Blue and white porcelain has its technological roots in 14th century Ming-dynasty ceramics, and it is created by painting designs with a cobalt-oxide mixture under the glaze. When fired in the kiln, the cobalt reacts to generate the distinctive sapphire blue colour. The best quality pieces of the Kangxi period are recognized for a bright blue design on a slightly-bluish white-glazed ground. Blue and white was used for both domestic consumption and for export outside of China.

It can be said that one would be hard-pressed to find an old European collection or a museum without at least a few of these pieces. A prime example would be the collection of August the Strong (1670-1733) now displayed in the Porzellansammlung in the Dresden State Art Collections, consisting of around 20,000 pieces of Chinese, Japanese and Meissen porcelain.

He was so obsessed with porcelain that he described himself as having a ‘maladie de porcelaine’, and given the quantity of blue and white porcelain found in European private collections, museums, and on offer in auction nowadays, it is certain that he was not the only one.

The term famille verte was coined in the 19th century and describes a group of porcelain that is decorated with overglaze enamels, dominated by colours such as translucent green and opaque iron-red, in addition to translucent yellows and blues, and opaque blacks.

These designs are often also embellished with painted gilt highlights. This palette evolved from the Ming-dynasty wucai (five colours) palette, which is why in Chinese it is called ‘Kangxi wucai 康熙五彩’.

The biggest difference between famille verte and wucai is the fact that wucai uses underglaze blue outlines infilled with overglaze red, green, yellow, and aubergine enamels, whereas famille verte does away with the blue outlines resulting in a more elegant and refined design.

Famille verte can be found in both porcelain and biscuit (lowfired) wares. The glassy green, blue, and yellow enamels used will often create a light iridescent effect around the design, what some would call a ‘halo effect’.

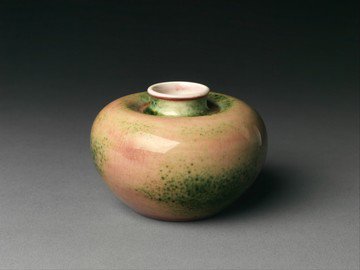

Another important development in Kangxi period porcelain is the mastery of underglaze copper red pigments. Copper pigments are very difficult to fire – instead of resulting in a rich red colour, the pigment can fire to lime green, or misfire into a burnt brown colour. Now with better kiln control, a ‘peach-bloom’ glaze was developed that is distinctive to Kangxi porcelain.

This glaze is identified by a mottled copper red (the colour of peaches), sometimes with a splash of light green where the pigment has oxidized in the kiln. Because peach-bloom glazes were produced mainly in the early Kangxi period and very often reign marked, they are greatly coveted by collectors and fetch a tremendous price on the market.

An excellent example of the mottled glaze can be found on a water pot (pingguo zun) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection, accession number 29.100.331.

A genuine peach-bloom-glazed beehive-form waterpot was sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 31 May 2017, lot 3012 for a hefty 2,040,000 HKD (including premium), so it is no wonder that there are more later copies than genuine on offer these days!

Artistically, the decoration on Chinese ceramics from this period can be characterised as freely painted and often depicting subjects such as: scholars in mountainous river landscapes; scrolling floral designs; elegant ladies; and scenes from popular stories.

These designs, particularly on export porcelain are densely painted, often with a central scene surrounded by a geometric patterned border, or, flower-petal-shaped panels.

Popular romances and epics such as ‘Romance of the Western Chamber’, ‘The Three Kingdoms’, and ‘The Water Margin’ were widely circulated at the time as woodblock printed books, which means that if one cares to look, many of the scenes on Kangxi porcelain are readily identifiable.

In addition to the standard forms of plates, bowls, teapots, and cups, some popular shapes of Kangxi-period Chinese ceramics include:

- rouleau vases: a fairly cylindrical body narrowing to a straight neck and galleried rim

- mallet vases: a type of bottle vase with a hoof-shaped body and a long cylindrical neck

- phoenix tail/‘yen yen’ vases: a trumpet-shaped vase with a flared neck, broad shoulders, and a flaring foot

- klapmuts bowls: a bowl shaped like an upside-down helmet with an everted straight rim

Another interesting aspect of Kangxi porcelain is the production of a whole catalogue of foreign shapes that would have been completely new to Chinese eyes. Because of the heavy trade between China and the Near East and the European West, potters in Jingdezhen were manufacturing forms such as English pudding moulds, Venetian glass bottle vases, and Islamic hookah bases.

It must be said however that the trade did not only go one way, we can easily see the influence of Kangxi blue and white on the development of the European ceramic industry, such as that in Delft.

Every specialist knows that it is not enough to just look at decoration. Handling a piece and assessing the actual porcelain body is also essential in determining authenticity. Kangxi porcelain tends to be comparatively thinly potted and the clay is well-levigated (minimal lumps and bumps).

The footrims are cleanly finished and when chipped, the porcelain within looks white. Kangxi porcelain is also recognisable by some common faults, such as:

- firing cracks: where the porcelain has cracked in the kiln

- glaze frits: where the glaze has flaked off the porcelain body, mostly occurring at the rims and sharp edges

- fine firing spots: small dark spots in the glaze due to ash in the kiln

Examples of all three these flaws can be seen in the images in this article. Of course, each piece will exhibit these characteristics in varying degrees, but keeping these points in mind is helpful in developing an idea of how a piece ‘should’ look and feel.

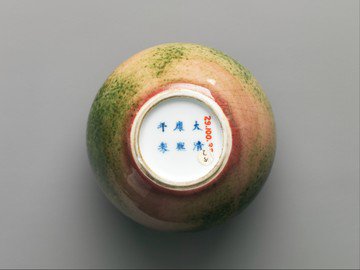

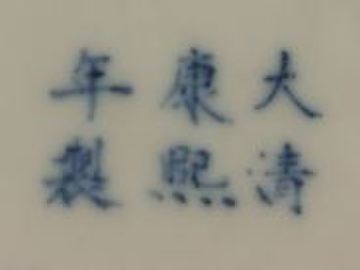

Kangxi-period marks can be loosely placed into two categories: reign marks and other marks. The former is the smallest in number and are almost always 6-character marks in kaishu (normal) script within a double circle.

The characters themselves can be described as spindlier or spikier than those of other emperors’, and the cross strokes (such as the horizontal strokes in the da 大,nian 年,and zhi製 characters) tend to sit higher on the body of the characters.

For the most part, the marks will be written in two vertical lines of three characters, though on a very small number of pieces such as the peach-bloom washer illustrated above, they are written in without the double circle in three vertical lines of two characters.

The appearance of four-character marks in this period are limited to top imperial wares, such as ‘month cups’ and falangcai (highest quality enamels) pieces. Knowing which types of pieces bear which style of mark is an essential skill in identifying potential inconsistencies in dubious Chinese ceramics.

The largest body of marks found on Kangxi porcelain have one of the following: no marks, pictorial marks, apocryphal marks, or blank marks within an underglaze blue circle. Because of the strictness in regulating his reign mark, potters employed alternatives such as having only an underglaze blue double circle, or an auspicious symbol, for instance an artemisia leaf, a lingzhi fungus, a precious object, or an auspicious character, such as yu (jade) 玉.

The most common apocryphal marks (marks referring to a previous ruler) found are those bearing the names of Chenghua and Jiajing emperors, and sometimes Wanli emperor. Various pictorial marks, including artemisia leaves, a fangding (ritual censer):

When presented with a piece, it is important to take into consideration the shape, the decoration and enamels, the porcelain body, and the mark (if there is one). Knowing what a genuine Kangxi-period mark looks like will help one spot the imitation marks that are found in 19th, 20th, and 21st century porcelain.

With regards to the 19th century, it is common to find underglaze blue four- and six-character marks on the bases of Guangxu period (1875-1908) porcelain.

The penmanship of these marks is significantly lower in quality and consistency than those in the Kangxi period, and the underglaze blue tends to ‘sit’ on the surface of the glaze. Modern vases, particularly famille verte vases, can also bear apocryphal Kangxi marks, and these marks have a stiffer feel, and the underglaze blue is slightly darker.

It is unknown for a seal mark to appear on a Kangxi-period piece, so it can be safe to attribute a piece with a seal mark to the 19th or even later.

Luckily because of the vast number of Kangxi pieces that exist today, it is one of the most easily accessible reign periods to study and handle, whether at museums, antique shops or at auction houses. Many pieces, in particular those made for export, can be purchased for affordable sums of money.

For example in recent sales, a blue and white dish decorated with flowers and cartouche borders can be purchased for between 30-50 GBP, and a klapmuts bowl (with an apocryphal mark) can set you back around 600-1000 EUR.

That being said, the highest quality Kangxi wares remain highly desirable. A blue and white phoenix tail vase from the Edward James Foundation was sold at Christie’s London on 15 December 2016 for a hammer price of 26,000 GBP, more than doubling a pre-sale estimate of 8,000 – 12,000 GBP. The joy of Kangxi pieces is that they are accessible at any step of the collecting ladder, and the variety of styles and decoration will surely appeal to any taste.

| Author - Denise Li | Denise is an independent Chinese art consultant who gained her experience as a Specialist at Christie's in London, UK after completing her studies in Chinese archaeology. She is currently providing specialist services to various auction houses and enjoys sharing her knowledge through writing for Antique-Marks.com |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.