The Qianlong Emperor 乾隆 (reigned 1736-1795):

The Qianlong Emperor e lived for 87 years, making him the longest living emperor of China. He also reigned for 61 years, making him the second-to-longest reigning emperor (his grandfather Kangxi emperor holds first place).

|

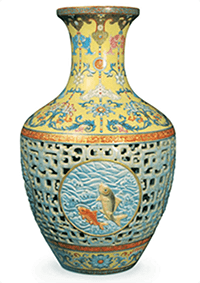

A vase dating to his period was sold in 2010 for £43 million in north-west London auction, making Qianlong porcelain one of the most expensive kinds of porcelain in the world today. |

What is Qianlong porcelain and what makes it so special?

For many, the Qianlong period is seen as the height of porcelain production. This is due to the unmatched quality and technique of the potters that worked in his imperial kilns at Jingdezhen. Here we can see a continuation of the revival of archaic and classical forms as favoured by his predecessor the Yongzheng emperor, as well as the combination and perfection of enamelling and moulding techniques.

Qianlong emperor had a taste for the extravagant, so with the exception of monochrome (single colour) pieces, porcelain particularly from the latter part of his reign was often highly and densely decorated. At times, the decoration borders on excessive; especially compared to the relative simplicity and elegance of the works from the preceding Yongzheng period

|

| A Qianlong famille rose water pot in the collection of the Gemeentemuseum, Den Haag - note the various design elements here: lavish enamelled and gilt bands, and meticulously pierced openwork dragon panels |

The kilns were creating pieces inspired by imitation, such as: pieces in archaic bronze forms such as tripod libation vessels (jue) and pear-shaped vases (hu); pieces covered in the classic crackle-suffused glazes inspired by Song-dynasty kilns; and pieces decorated with cobalt blue in the ‘heaping and piling’ effect mimicking Yuan- and Ming-dynasty blue and white porcelain.

Not only did Qianlong draw from history, he also used nature as a template, commissioning realistic porcelain imitations of wood and bamboo, bronze, cloisonné enamel, stone, and so on.

Famille verte, which was the decorative palette of choice in the Kangxi period (1662-1722), was no longer in vogue. Popular palettes were blue and white, famille rose (often with gilt highlights), and doucai. Popular subjects were flowers, birds, figures, dragons, and landscapes. What also strikes one in porcelain and art from this period is the presence of European influence.

It was in this period that Giuseppe Castiglione, a Qing court painter and an Italian Jesuit, was commissioned to build Western-style mansions and pavilions in the Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan) introducing effects in perspective such as trompe l’oeil, and the French Father Benoist was commissioned to design water fountains modelled after those in Versailles and similar estates.

|

| Note the European form of this Qianlong blue and white sauceboat decorated with flowers, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag |

Qianlong porcelain can be broadly divided into three categories: guanyao (imperial), minyao (porcelain for the people), and export. Guanyao and minyao porcelain share many of the same glazes, shapes, and designs. This category encompasses pieces such as monochromes (pieces glazed with a single colour which are appreciated for their elegance of form and richness of glaze) and the aforementioned ‘imitation’ pieces.

Pieces that bear decoration often feature auspicious imagery such as: dragons and phoenix; deer and cranes; and birds and flowers. Many of these combinations represent rebuses (pictorial sayings) wishing the owner success and fortune. Some excellent examples of guanyao and minyao are housed in the British Museum from the collection of the Percival David Foundation.

|

| Three late Yongzheng-early Qianlong-period (c. 1720-1750) monochrome and crackle-glazed vases with European mounts, Rijksmuseum nos. AK-RBK-17520- A and BK-16909-A and B |

Qianlong was an ardent patron of Tibetan Buddhism, so it is not surprising that some exceptional pieces exist in the form of finely modelled and brightly enamelled Buddhist stupas and altar vessels. It is no wonder that these pieces fare well in the market, for instance, a famille rose figure of the Buddha Amitayus was sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong on the 8 April 2013 for a price of $8.4 million HKD (including buyer’s premium).

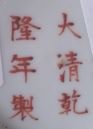

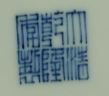

The vast majority of marks on Qianlong porcelain are written in zhuanshu, seal script. It is uncommon for porcelain to be marked with a kaishu (normal script) mark; this style of mark is more common in painted enamels, bronzes, lacquer and glass. Qianlong seal marks tend to be written or incised, and can be executed in underglaze blue, iron-red, or gilt.

Both guanyao and minyao pieces can bear these marks, and what separates the two is the quality of the porcelain and the finesse of the decoration and the mark. The marks on guanyao pieces tend to have regular, well-proportioned brush strokes, whereas minyao pieces tend to have slightly more irregularly-written marks.

Interestingly, although Qianlong emperor loved to emulate the past in the forms and designs of his porcelain, when it comes to reign marks, we do not see apocryphal marks from this period bearing the names of previous emperors.

Regarding the third category, a tremendous amount of porcelain was produced for export to the West – wealthy Europeans and Americans would order vast quantities in the form of dinner services, tea and coffee services, basins, punch bowls, and sets of vases (garnitures).

Decoratively speaking, figural scenes are often enclosed by patterned borders with bird and flower cartouches; floral décor would be characterised by large central blooms surrounded by busy shaped borders.

|

| A famille rose ‘Mandarin Pattern’ bough pot in the Rijksmuseum collection, no. AK-NM-6941-2. The figural decoration, bird and flower cartouches, and the European shape are all typical of Qianlong period |

The most distinct designs from this group would be those depicting European figures, religious and mythological scenes taken from engravings, and scenes based on drawings by Cornelis Pronk, a draughtsman employed by the Dutch East India Company between 1734 and 1740. He produced sought-after and recognisable designs such as the ‘Dame au Parasol’ and the ‘Doctor’s Visit’.

A further group treasured by collectors is armorial porcelain, which are pieces ordered by the richest families in Europe and America emblazoned with their coat of arms and in the latest styles. Finally, an entertaining and interesting development in this period was the rising popularity of porcelain figures and models of animals such as dogs, boars, and birds, all which would be displayed in cabinets and on the dining tables of the wealthy.

Authenticity-wise, is important to bear in mind that because this category of porcelain was made for foreign trade, export porcelain does not bear reign marks.

|

| A Qianlong-period flask in the shape of a Dutchman – interestingly, these flasks were based upon 18th century European faience and Delftware originals |

Because of the admiration that Qianlong commanded as an emperor and the superb quality of his porcelain, it is no surprise that we can find Qianlong marks on pieces made both during and after his reign up to modern day. Because of this, the form and the decoration should be looked at first, and then the mark (if present) should be used as a piece of back-up evidence.

For example, the below apocryphal Qianlong mark belongs to a 19th century coral-ground double-gourd vase. We know that the mark is apocryphal because of the form of the vase and the colour of the enamels (the coral-red and the turquoise) do not match the shades found in the 18th century.

|

| An apocryphal Qianlong six-character seal mark on a 19th century vase |

Qianlong marks written in normal script (kaishu) and stamped seal marks were popular in the Guangxu period (1875-1908) and later. The use of the Qianlong mark continued through the Republic period (1912-1949), and many pieces from this period bear four-character marks written in blue enamel, or seal marks in gilt.

|

| An apocryphal Qianlong six-character mark on a Guangxu-period (1875-1908) bowl |

|

| An apocryphal Qianlong stamped seal mark on a 20th century vase |

Buyer beware! Due to the fact that mark and period pieces from the Qianlong period command such high prices, porcelain from this reign is one of the most popular for forgers. Though specific advice regarding marks is indeed helpful (such as a ‘real’ mark should have five prongs on the zhi 製character, or the bottom left of the Qian 乾character should look like a ‘5’), this advice should be taken as a hint, rather than a solution – just take the two marks below as an example.

Nowadays fakers study genuine pieces just as much as collectors and are so meticulous with their forgeries that there are indeed modern copies bearing all the right features.

|

| Qianlong six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1736-1795) |

|

| Apocryphal Qianlong six-character seal mark in underglaze blue on a 20th century dish |

Just because a piece bears a Qianlong mark does not necessarily mean that it belongs to the period. It is important to look at the piece as a whole and ask questions such as:

- Should the piece have a mark, and if so, does the decoration on the rest of the piece fit with the 18th century aesthetic?

- Does the enamelling look right for its age?

- Is the decoration done by hand and is it well-executed? Are the enamels the right shade? For example, is the iron-red a shade of coral rather than a nail-polish red?

- Does the mark sit in the centre of the surface?

- There should be the same amount of space between the edges of the mark and the edge of the piece

- Is the size of the mark proportional to the size of the surface?

- The mark should not be too big nor too small – this eye for proportion comes with experience

Because of the plethora of porcelain made in this period, the price of Qianlong porcelain can range from the tens to the millions. As with Kangxi porcelain, export pieces tend to be on the affordable end of the price scale.

A simple famille rose dish decorated with scattered flowers would cost around £25-50, and a blue and white tureen and cover will fetch around £600-1000, and for the connoisseurs of this category, a famille rose armorial snuff box was sold at Christie’s New York for $15,000 in January 2017.

Guanyao imperial pieces represent the top end of the market, and there is where the real excitement happens. As mentioned at the start of this article, in 2010, a Qianlong mark and period famille rose yangcai vase shocked the world by selling for a record £43 million at Bainbridges, a local auction house in England. What had followed was also shocking – three years later the piece remained unpaid by the buyer, resulting in a deal brokered with an alternative buyer for around half of that sum.

In May 2017, a pair of famille rose ‘butterfly’ vases, also mark and period, was sold at Christie’s London for £13 million (hammer price). What makes this story thrilling was the fact that these vases had been previously been judged to be of a later date and valued at under £1,000! It is truly astonishing to see the effect of a ‘mark and period’ designation on the market price of an object

|

| A famille rose ‘butterfly’ vase sold at Christie’s (one of a pair) |

|

| Qianlong six-character seal mark and of the period |

As with all Chinese works of art, it is important to be vigilant and to use not only your eyes, but also your touch, and most of all your brain. The more genuine pieces you encounter, the easier it is to separate the old from the new.

Luckily, Qianlong-period porcelain is displayed in museum collections around the world and comes up regularly for auction, so there are many opportunities to get acquainted with the art which has (with good reason) captivated collectors around the world for almost three hundred years.